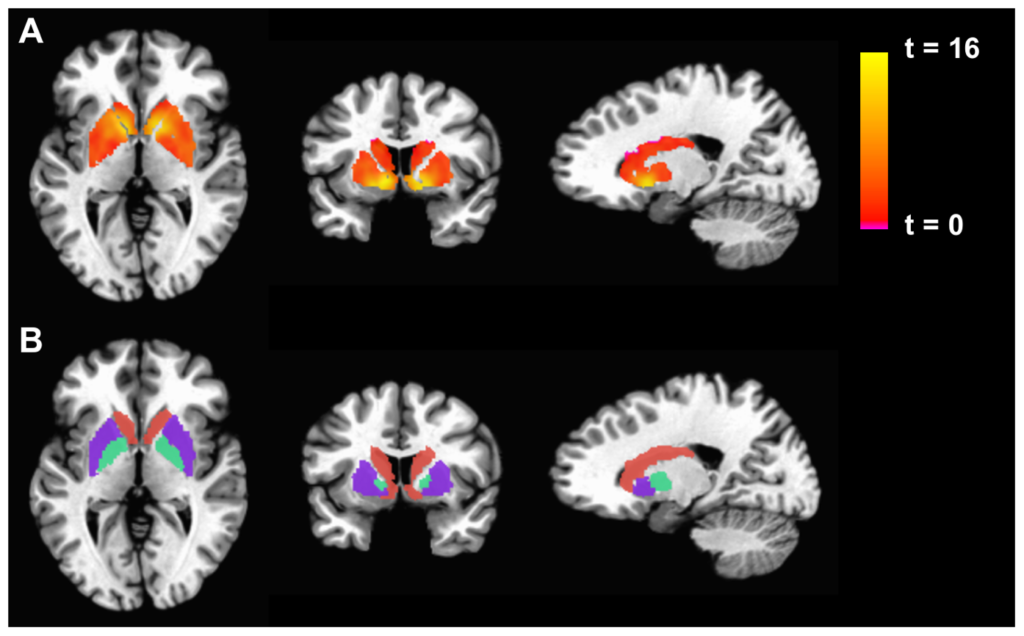

Figure 1: fMRI is used to display differences in basal ganglia activation between individuals with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and control subjects—precisely the type of analysis that will be more difficult to accurately perform in light of newfound limitations to fMRI reliability. 1

The term “fMRI” has over two hundred thousand mentions in PubMed. From surgical planning to post-treatment monitoring to pharmacological biomarking, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a central tool in the scientific research community. Recently, however, a team of researchers at Duke University took a closer look at the imaging technique and arrived at a troubling conclusion: fMRIs might not be as helpful as once thought.2

The idea behind fMRI is simple. Magnetic resonance detects changes in cerebral blood flow, which serves as an indicator of neural activity. fMRI allows scientists to understand which regions of the brain are especially active in an individual’s mind at a given time. The technology has allowed for examination of the brain’s functional anatomy, evaluation of the effects of injury or disease, and detection of brain abnormalities often missed by other imaging techniques.3

Functional MRI is also commonly used as a biological indicator for diagnosis of disease— this is where the new findings about fMRI become an issue. In essence, the Duke University research team found that while fMRI remains a useful tool for identifying active brain regions during a single scan, the test re-test reliability of two different fMRI scans is astonishingly low. This means that the fMRI scan of an individual performed as they complete a memory task or watch a film, for example, could easily be entirely different when tested under the same circumstances a week later. For a biological measure to be an effective indicator of health, patients cannot test randomly high on a measure one week and low the next; the test-retest reliability must be high enough that changes in data can be trusted to signal changes in health. As the Duke research team reveals, fMRI falls short in this respect.2

To determine the reliability of fMRI scans, Dr. Ahmad Hariri, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, assembled a team to reexamine fMRI data from two large-scale imaging studies: The Human Connectome Project and the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, both of which included task-based fMRI data obtained twice, months apart, from the same individuals. The team also reexamined the test-retest reliability of fMRI data from 90 different experiments in 56 published papers. The results, according to Hariri, spoke for themselves: “the correlation between one scan and a second is not even fair—it’s poor.”4

According to Russell Poldrack, a professor of psychology at Stanford University and the author of one of Hariri’s reexamined studies, suspicions about fMRI reliability have existed for some time.4 A small body of existing fMRI reliability research attests to his assessment. However, as Hariri explains, many of the early reliability studies were underpowered and contradictory. A large-scale analysis was sorely needed, and Hariri’s work did the job.

While the lack of reliability will limit the use of fMRI imaging as a biomarker for disease diagnosis and progression, the technology is far from becoming extinct. Both Poldrack and Hariri predict that longer imaging periods (hours instead of minutes) and more comprehensive connectivity mapping (between regions opposed to within them) could pave the way forward for more effective use of fMRI data.4

Poldrack declared the findings “a good wakeup call” for the scientific community.4 For the rest of us, Hariri’s work offers a jarring example of the ever-changing scientific world and underscores the importance of continual curiosity—even about those unassuming “known quantities.”

References

[1] Decreased Basal Ganglia Activation in Subjects with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Association with Symptoms of Fatigue. (2014). PLOS ONE, 9(5), e98156. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098156

[2] Elliott, M. L., Knodt, A. R., Ireland, D., Morris, M. L., Poulton, R., Ramrakha, S., Sison, M. L., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., & Hariri, A. R. (2020). What Is the Test-Retest Reliability of Common Task-Functional MRI Measures? New Empirical Evidence and a Meta-Analysis: Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620916786

[3] Glover, G. H. (2011). Overview of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Neurosurgery Clinics of North America, 22(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2010.11.001

[4] Studies of Brain Activity Aren’t as Useful as Scientists Thought. (n.d.). Retrieved July 2, 2020, from https://today.duke.edu/2020/06/studies-brain-activity-aren%E2%80%99t-useful-scientists-thought

Related Posts

Twin Impacts of the Chernobyl Disaster: Birth Defects and Mental Health

Figure 1: Damage caused to reactor 4 of the Chernobyl...

Read MoreThe Gut May Be The Door to Effective Depression Treatment

First Author: Jillian Troth1 Co-Authors [Alphabetical Order]: Roxanna Attar2, Caroline...

Read MoreNew ALS Treatments in Development: Stem Cell Therapy and Neuronal Replacement

For more neuroscience news, check out Akshaya’s organization on neuroscience...

Read MoreAudrey Herrald